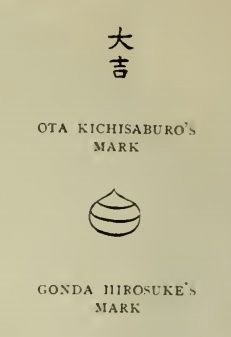

CLOISONNE ENAMEL-WORK. BY PROF. JIRO HARADA

(Part Two)

The shippo industry is already suffering a heavy penalty – at least that class of ware which depended solely upon the capricious demand of the West coexistent with ignorance of the Japanese and their artistic ideals.

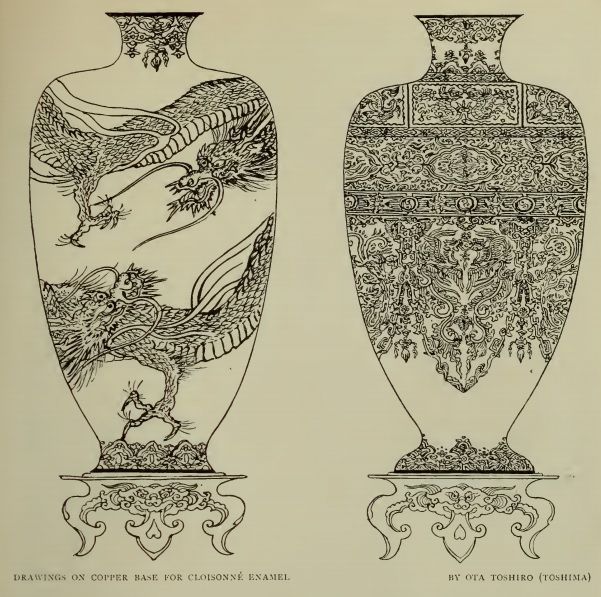

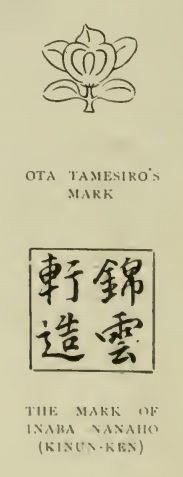

Let us take as an illustration the case of Toshima, a village a few miles from Nagoya. It is known properly by another name, that of Shippo Mura, which means "village of cloisonne wares," because directly Kaji Tsunckichi, a native of the village, rediscovered the forgotten art of cloisonne manufacture and started its modern development, the whole village–of a considerable size–turned its entire attention to this industry, each craftsman guarding his own secrets and discoveries, until at one time the inhabitants of Shippo Mura turned out no less than seventy per cent, of the total cloisonne enamels produced in Japan. But nearly all the kilns in Toshima are now idle and their workshops closed, while the annual output of Japanese cloisonne has dwindled during the last six years to less than one-third of what it used to be.

The appearance of the village was almost unbearable to the writer when he re-visited it nearly two years ago, and remembered the thriving state of affairs that had greeted his eyes on the occasion of his former visit made several years before. The whole aspect of the place suggested something little short of a tragedy. While we are conscious of various other causes (one of which we shall deal with later) contributing to this downfall, it is our belief that the keynote of the tragedy lies in a misconception of Western needs and the flooding of Western markets with cheap, low-class wares. This mistake dates especially from the time of the Paris Exposition in 1900 and was carried on until the close of the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904.

It was in that period that an enormous amount of cheap gin-bari was made at Toshima and sent out of Japan. This was the immediate cause of the decline and was assisted by a better knowledge of things Japanese on the part of the buyers.

It must be stated, however, that some fine specimens of this work are still being produced, although the practical ruin of the industry at Toshima indicates the general decline of the enameller's art as an industry throughout Japan. For the production of shippo ware there have been three centres, speaking in reference to the locality in which they are produced–Nagoya and its vicinity, Kyoto, and Tokyo, the last two places having learned the art from the first, where the bulk of cloisonne enamels are still produced at the present day.

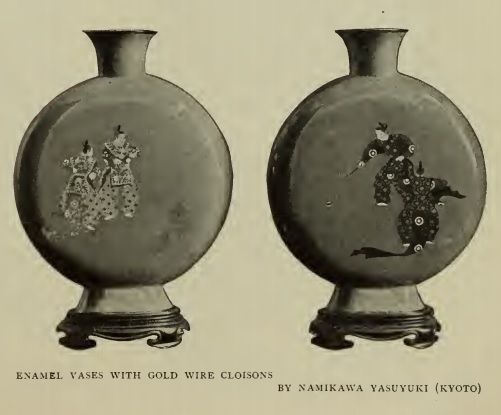

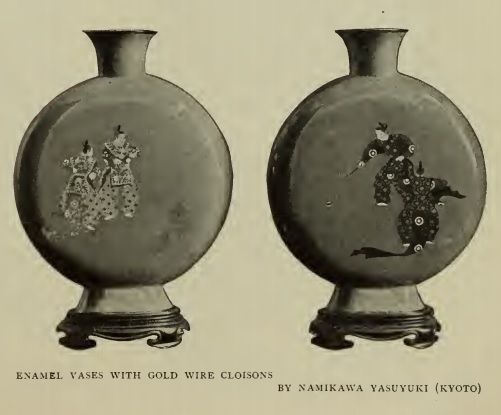

It may be well to note that there is a certain class of work known as "Kyoto Jippo" in which the whole surface of the piece is generally covered with decoration of gilt wire, which used to be the characteristic production of Kyoto, while in the product of all other branches the artist aimed chiefly at pictorial effect, placing a design in a monochromatic field of a pale or dark tone. But "Kyoto Jippo" has long been manufactured at Toshima, where every variety of shippo ware has been successfully produced.

Thus, although the local peculiarities of the product have largely disappeared, it will still be of some interest to observe a few salient points in the life and work of famous shippo artists of more recent times who are to be found in these localities.

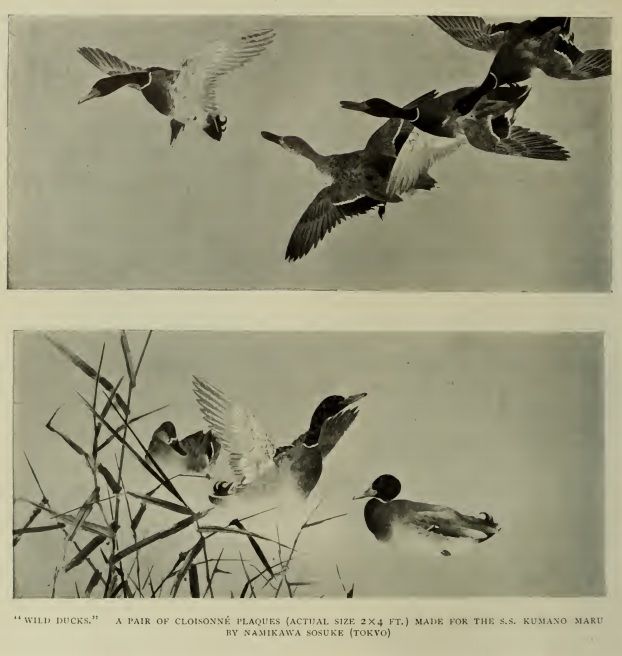

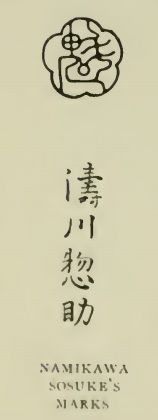

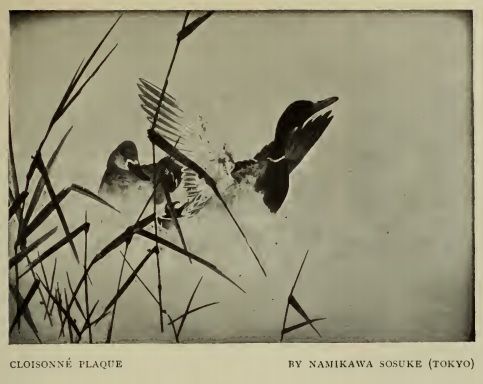

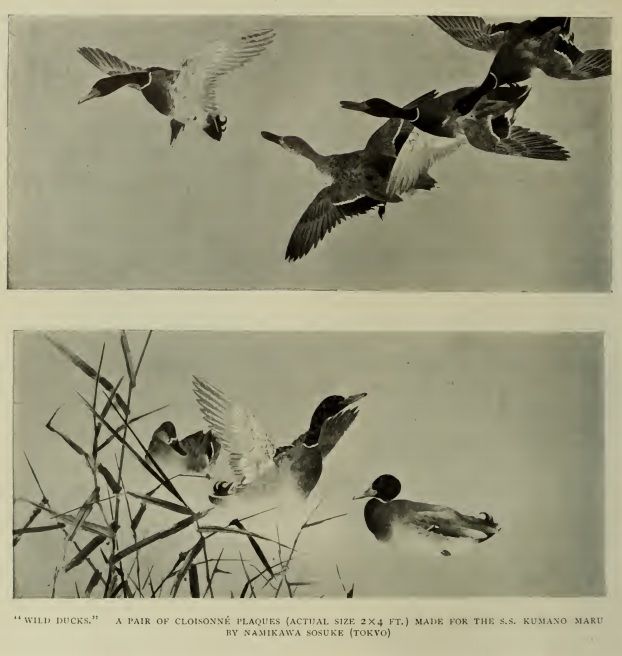

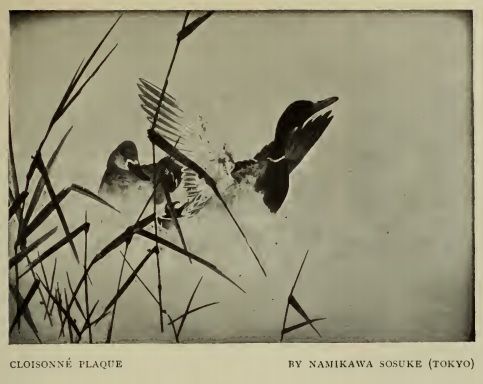

Tokyo–if, indeed, we may not say Japan–has never had a greater shippo artist than Namikawa Sosuke, who died a year ago last February. Credit should be given to him for first elaborating a device by which a large surface of the piece is covered with monochromatic enamel without the use of cloisons. Namikawa Sosuke is also credited with the invention of musen Jippo, or " cloisonless enamel." The excellence of his workmanship in this particular method can well be discerned in the thirty-two plaques now decorating the walls of the palace of the Crown Prince of Japan. Moonlight on the Sea and Wild Goose under the Moon, two plaques in musen which were exhibited at the Palace of Fine Arts at the Japan-British Exhibition, are some of his last triumphs in the execution of difficult subjects by a still more difficult method. His work is now carried on by his grandson, and there is no one else in the capital whose work has any distinction.

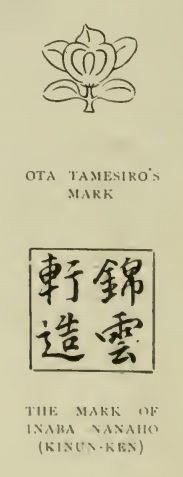

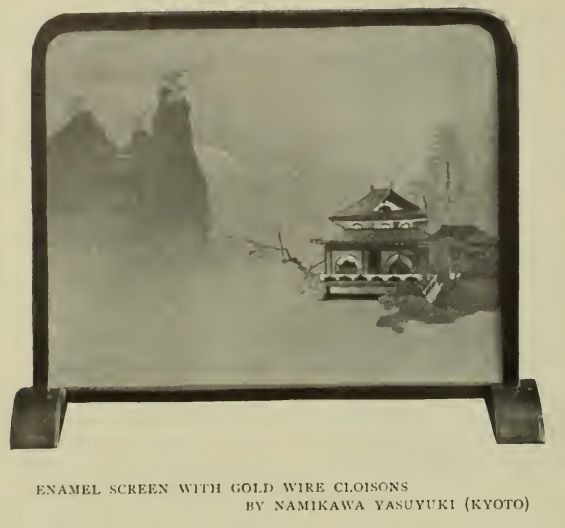

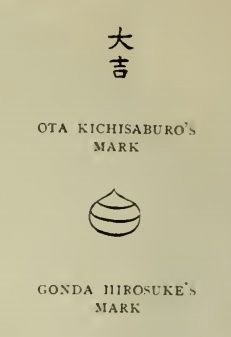

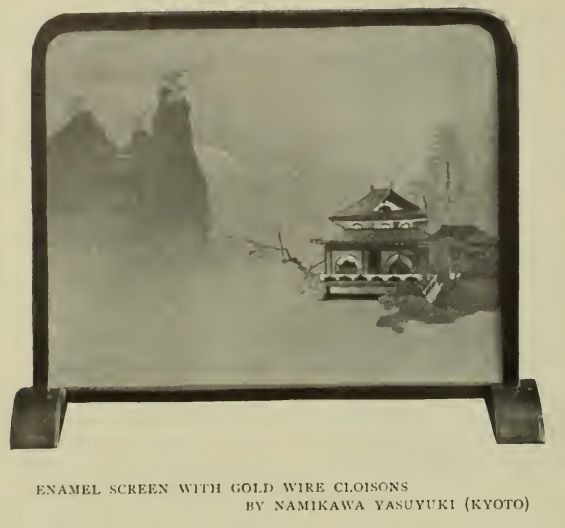

While there are in Kyoto a few shippo artists of some note, such as Takahara Komajiro–who continues to produce " Kyoto jippo " and has recently made some considerable improvement in the ware, giving it the appearance of damascene work and Inaba Nanaho, who produces some excellent specimens of gin-jippo and yusen-do-jippo with intricate work in wires, none have excelled Namikawa Yasuyuki (or Seishi) in the utmost delicacy of craftsmanship and perfection of technique, in purity of design, harmony of colour, and subdued tone. Some of his marvellously minute workmanship can best be appreciated under a magnifying glass, bespeaking his endless patience and the faithful quality of his labour. He has never lowered his standard of production. His work is strictly high class, and he excels in the employment of fine gold wires in the most intricate of designs. He is the only Court artist now living among the shippo manufacturers.

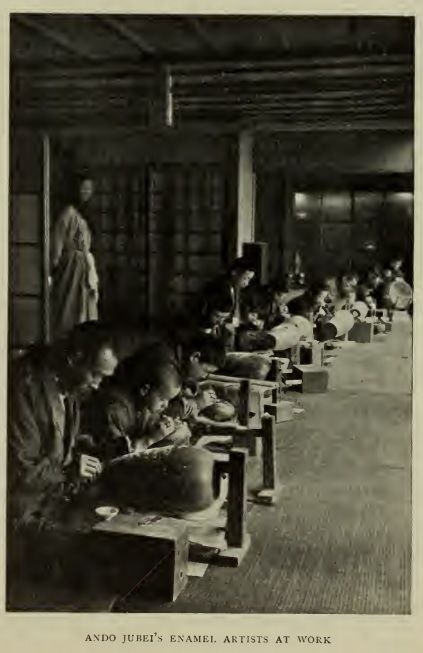

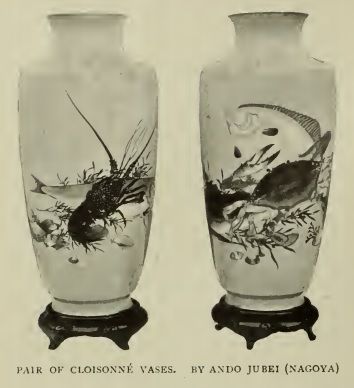

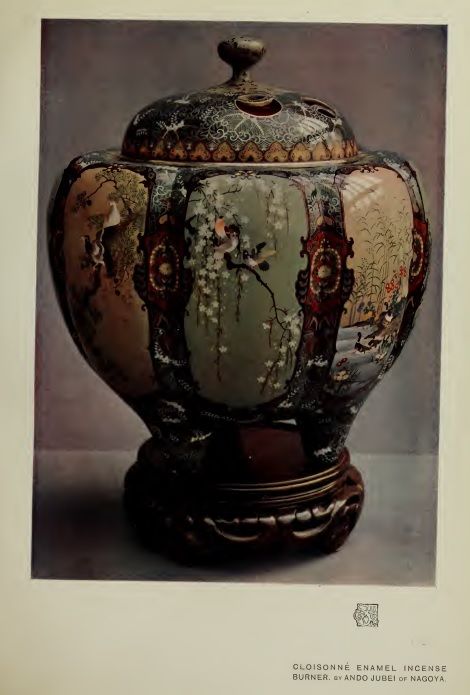

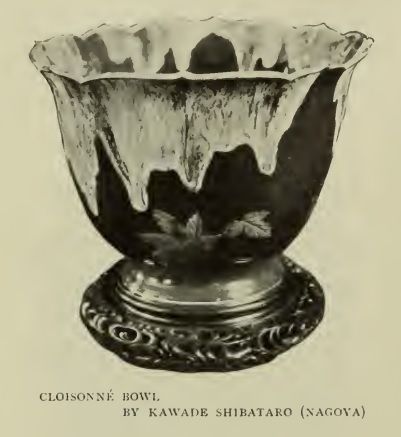

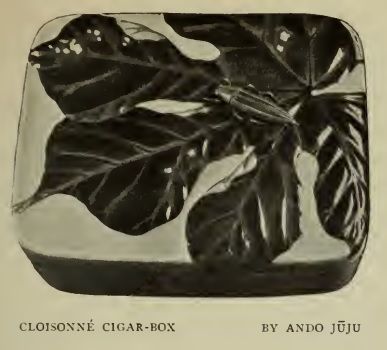

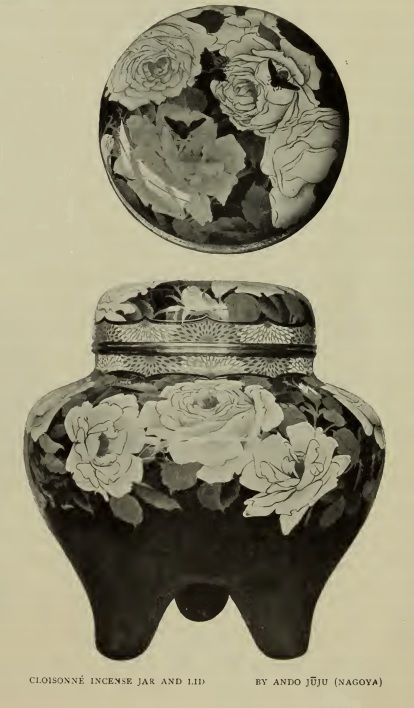

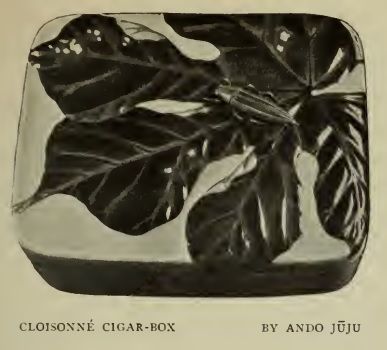

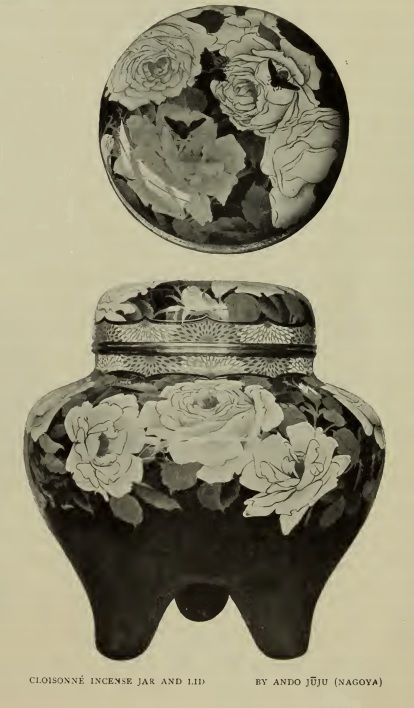

A few names, at least, must be mentioned in connection with Nagoya. Perhaps the best-known Japanese shippo manufacturer is Ando Jubei of that city. He and his brother Juju have done much for the encouragement in this art industry. It was late in 1881 when Kaji Sataro, a grandson of Kaji Tsunekichi (already referred to), came to Ando for his assistance, as Kaji Sataro was unable to carry on his business ; and that was the beginning of Ando's engagement in the present undertaking. Ando's rare insight in noting what is best suited for the time and his valuable judgment of colour and form, together with the talent to get the best out of each of the large number of expert enamel artists that came to work for him, enabled him to send out unusually good specimens of shippo ware. He has one large factory, but he also has many artists in different parts of Nagoya and Toshima working exclusively for him. But his reputation was established chiefly by the splendid work turned out by his chief enamel artist and designer, Kawade Shibataro, who is deservedly considered the greatest enamel expert in the manufacture of shippo at the present time. Perhaps no other living person has done more towards the improvement of Japanese enamels and the invention of new methods of application than Kawade. He has been engaged in the shippo industry for the last forty years, and the advantage of his scientific knowledge and his indefatigable devotion to the work have enabled him to invent new colours in enamels. Both uchidashi and moriage' are the result of his untiring efforts. Kawade has recently found a novel way of decorating his pieces with rainbow-coloured porcelain-like glaze called nagare-gusuri. He also excels in the production of musen jippo.

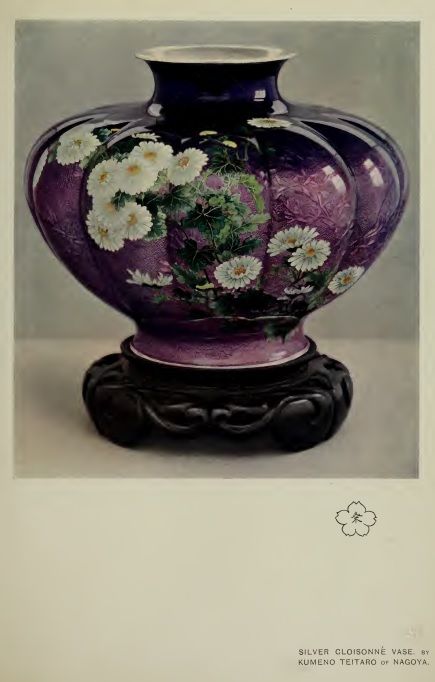

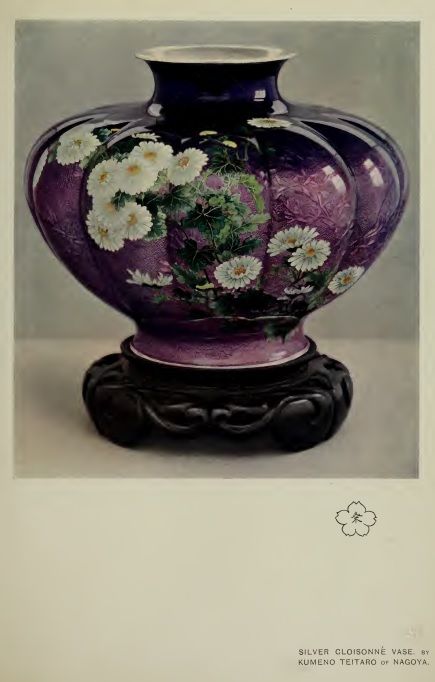

Mention should also be made of Kumeno Teitaro (or Shimetaro) of the same city. While the honour of being the inventor of gin-jippo (silver cloisonne)

is claimed by many, the success of gin-jippo is no doubt due to Kumeno's discovery of a method that prevented the enamels covering the silver foundation from getting cracked in the course of a year or so, as was formerly the case. According to Kumeno's own story related to the writer, he happened to notice, while waiting for a train at the station one day, that a considerable space was allowed where the rails were joined. When it was explained to him that the space was necessary for the expansion of the steel in heat, an idea flashed through his mind that the difficulty with gin-jippo might lie in the fact that the silver base was too thick to allow of a uniform contraction and expansion of the metal with the enamel covering it. He began hammering the silver base very thin, and the result proved satisfactory.

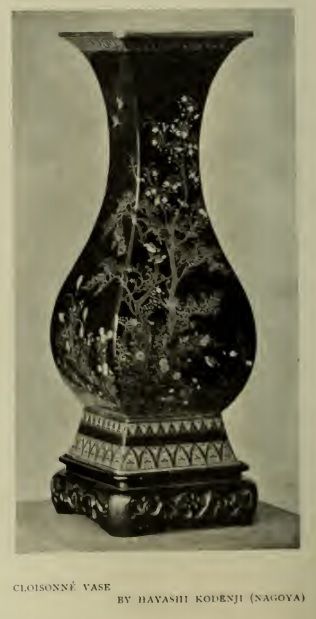

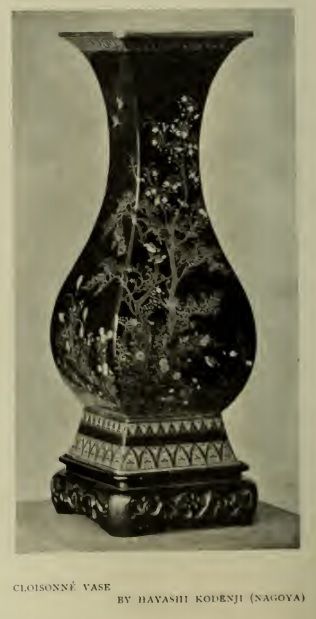

Hayashi Kodenji of Nagoya, now eighty years old, is another great benefactor of this art industry. How devoted he was to his art will be recognised when it is remembered that he exhausted his ample wealth in struggling to manufacture and improve shippo, and that in order to obtain further capital for his work by selling his productions to foreigners at Yokohama (though it was unlawful then to sell gold, silver, copper or iron to the foreigner) he walked the whole distance of nearly five hundred miles from Toshima to Yokohama and back, disguising himself as a silk merchant, and carrying his shippo in cocoon baskets suspended from the ends of a pole across his shoulders. His wares are still noted for the excellent quality of their monochromatic enamel and for faithful technique.

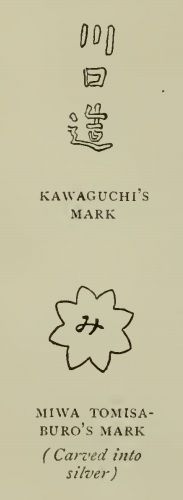

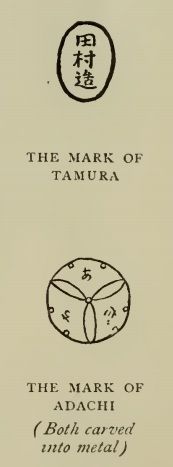

Again, there is Hattori Tadasaburo, noted for the shotai-jippo or "transparent cloisonne " ; Hayakawa Kamesaburo and Ichikawa, the best manufacturers

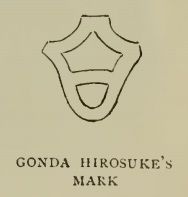

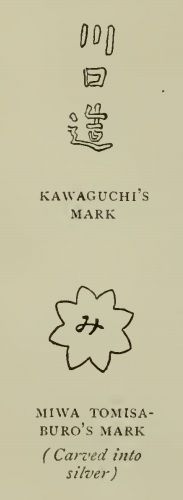

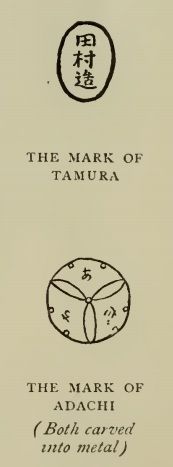

of akasuke : and such others as Miwa Tomisaburo, Tsukamoto Tojuro of Toshima, Gonda Hirosuke, and Kawaguchi Bunzaemon. But space does not permit a detailed account of them and their work. Suffice it to note here that Nagoya is still the centre of the shippo industry, which is one of the principal industries of Owari province.

The characteristics indicated in the quality of this work in cloisonne enamel and its development are unswerving devotion and steadfastness of purpose,

combined with a spirit of sacrifice, entailed by the lack of scientific methods of investigation. A glance at the history of any of the shippo artists will be sufficient to convince us of the extreme hardships encountered by the craftsmen in trying to obtain a result by haphazard yet infinitely laborious experiment, always with the hope that the patient worker might be fortunate enough to hit on a new and valuable secret. They wooed chance with loyal constancy, taking every rebuff cheerfully. Two or three concrete instances which illustrate the strange conditions under which Japanese enamellers have developed their art may be mentioned. First, the chance observation at a railway station by Kumeno, already alluded to.

Then the case of the craftsman who stumbled on the secret of chakin (tea gold) while experimenting with copper, some shavings of which fell into the molten enamel and gave an exquisite golden lustre.

Another instance was the discovery, by a mere smell of burning wood, of a grey enamel by Hayashi while he was working under Dr. Wagnel in Tokyo, to whom the enamellers of Japan as well as porcelain manufacturers owe so much of their success. Such stories might be multiplied, but these should be sufficient to indicate the somewhat haphazard way in which the shippo artists arrived at their most treasured secrets, though they worked with great constancy of purpose.

At the same time another national trait may be discerned, namely, the love of overcoming difficulties, which leads to the adoption of a more difficult method even at the expense of its effect upon the art itself. As the manifestation of this idiosyncrasy in Japanese music has been somewhat disastrous, it is to be feared that shippo may suffer in like manner. Are not musen and nagare-gusuri, whose characteristics consist in the heroic achievement of effects properly inconsistent with cloisonne art, clear manifestations of this idiosyncrasy ? The artist is in danger of becoming merged in the clever craftsman, and the art itself of being lost in the pursuit after enormously difficult technique. However, it is perhaps merely a matter of taste.

But it is people's taste that often determines a vital point in art. The difference in the points of view from which East and West appraise and appreciate an art object is another factor which may have serious effects. In Japan the object is admired or condemned chiefly on its own intrinsic merits without regard to its decorative appeal. Most of the articles decorating our tokonoma are decorated, not decorative, art objects, whereas in the West the decorative quality is nearly always demanded. As is the case with many other Japanese works of art, much of the best cloisonne depends for its appeal on fine workmanship, which can only be appreciated on close examination, and it has but little value as a decoration in a room. As the cloisonne industry depends largely on its Western markets, this difference in the point of view between the artists who produce it and the people who buy it is bound to present a serious difficulty.

The problem is whether the characteristic Japanese genius for fine workmanship can be made to produce a definitely decorative object suitable for ornament in a Western home, without sacrificing both the Japanese artistic ideal and the essential characteristics of cloisonne art.

Such problems are not confined to the future of shippo art. They confront the new Japanese art, which aims at the perfect harmonisation of the best in Occidental art with the best in Japan's own art. Not the least interesting phase of such a problem will be to determine the value of technique in relation to its effect on art, especially in a country like Japan where particular importance is attached to the spiritual and idealistic side of art. Suffice it to note here that there is a strong tendency even in shippo art to aim at that which is most difficult regardless of the effect obtained.

Jiko Harada.

Source:

The International Studio - 1911

Trev.